Understanding the Federal Excise Tax on Heavy Trucks

Share this Article:

For anyone in the trucking industry, maintaining accurate taxes associated with trucks is critical but not always simple. Because some of these taxes, including the federal excise tax, are so high, it is critical to get them right (failure to do so could result in financial losses through fines.)

What Is the Federal Excise Tax on Trucks?

The federal excise tax is imposed on some goods and products, including gasoline and cigarettes. Most of the time, these taxes occur at the time of purchase. The trucking industry has its own tax. It’s applied at the point of purchase of a truck and tractor. It applies to any vehicle that falls under their definition of a highway vehicle designed to transport loads on the same chassis as the engine, even if it is equipped to tow a vehicle. This includes semitrailers and trailers. It only applies to larger trucks, not the typical type that consumers might purchase.

The federal excise tax also applies to tractors, which the government defines as highway vehicles designed to tow a vehicle, including a trailer or semitrailer. The seller is liable for paying this tax at the time of the purchase. Understanding how this applies to you could be critical to ensuring your business remains tax-compliant.

Determining Taxable vs Exempt Vehicles

The Federal Excise Tax (FET) is imposed on the “first retail sale” of the truck after its manufacture or production, except for resale and long-term lease trucks. The tax, which is 12%, is levied on truck chassis exceeding 33,000 pounds. It also applies to trailers and semitrailers if they exceed 26,000 pounds and on tractors of 19,500 pounds or more and have a combined weight of more than 33,000 pounds.

The truck seller is responsible for collecting and reporting the taxes. You must submit quarterly documentation of these taxes through IRS Form 720.

Calculating Federal Excise Tax

To calculate the federal excise tax, apply the rate listed in the Internal Revenue Code Section 4051. At this time, it is 12%. That means the seller must collect 12% of the retail sale price on the taxable item at the time of purchase.

You must then submit Form 720 on the appropriate due date based on when the sale occurred. It must be submitted within the quarter:

- Sales in January, February, and March must have Form 720 submitted by April 30th of that year.

- Sales from April, May, and June must have the form submitted by July 31st.

- Sales that occur in July, August, and September are due to be paid by October 31st.

- Sales in October, November, or December must be paid by January 31st of the following year.

Common Challenges in FET Tax Compliance

Some factors can make the FET complicated or confusing. Here are a few things to keep in mind.

Used trucks

The federal excise tax does not apply to used trucks. It only applies to the first retail sale of the truck.

Imported trucks

If you export a truck as a dealer and then import it again to make a sale, even if it is a used truck, that will be taxed. It is considered the first sale of the truck.

Exemptions

Several sales could be exempt from this excise tax, including:

- Sales to Indian tribal governments, only the transaction involving the exercise of an essential tribal government function

- Sales to a state or local government for its exclusive use

- Sales for use by a purchaser for further manufacture of other taxable articles

- Sales to a qualified blood collector organization for the collection, storing, or transporting of blood

- Sales for export or resale by the purchases to second purchases for export

- Sales to the United Nations for official use

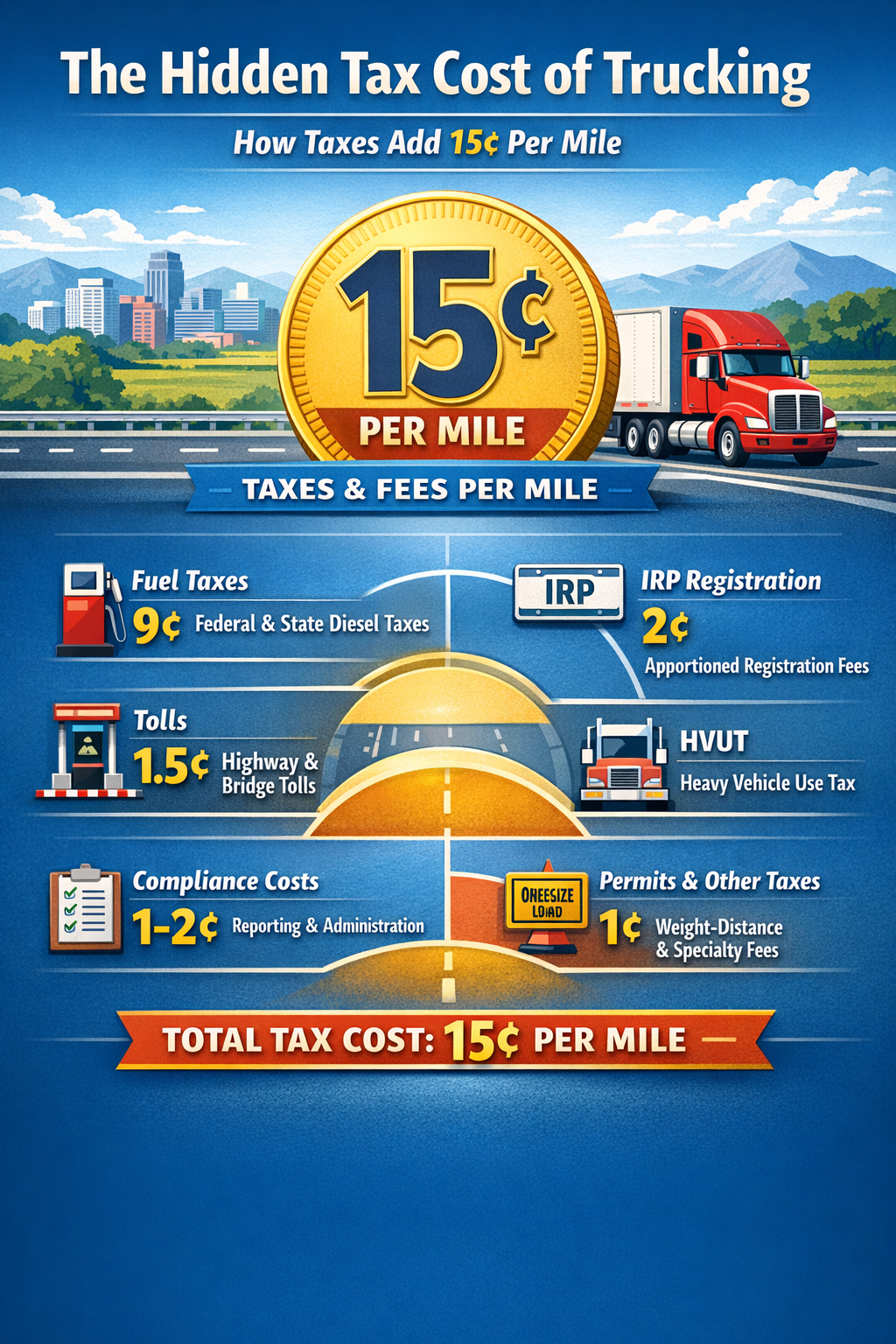

Heavy Vehicle Use Tax

The truck owner or buyer is responsible for filing and paying the Heavy Highway Vehicle Use tax through Form 2290. This is an annual tax to continue the use of heavy, load-bearing vehicles. This applies to trucks that weigh 55,000 pounds or more.

Best Practices for FET Tax Compliance

- Remain compliant by staying up to date on the laws and changes to them. The tax code could change in any year, and it is your responsibility to make payments accurately and on time.

- Keep accurate records of all taxes collected. It is the seller’s responsibility to collect and maintain these taxes for payment on the date listed above. If you do not have this information, it could be critical and costly.

- Determine if any tax credits apply. In previous years, tax credits have helped reduce costs.

- Instruct the purchaser of the truck, who is paying the tax credit, to reach out to their accountant to document and maintain these costs for their own tax purposes down the road.

- Note that other taxes may apply as well, including other federal excise taxes. This is often on fuel, heavy vehicles, and communications.

Key Takeaways for FET Tax

Any business that sells a truck, one that could be considered used as a highway vehicle, must require payment of the federal excise tax at the time of the purchase. The buyer pays that time at the time of the sale, and the seller collects and reports those funds to the IRS. As with any type of tax filing and documentation, it is critical to get it accurate. If you make any type of mistake, such as errors in the figures you use, that could lead to financial losses down the road – including fines for not collecting accurate taxes.

Find the Best Savings Opportunities for You

If you are a transportation business, you have several financial hurdles to overcome on a routine basis. Get some help navigating the process. Contact Transportation Tax Consulting today and let us help you with tax credits, tax breaks, and the federal excise tax you must collect when selling a truck. Contact us now to learn more.

Share with Us: